STRANGE WAY OF LIFE & THE HUMAN VOICE

A Pedro Almodóvar short-film double feature with STRANGE WAY OF LIFE (2023) and THE HUMAN VOICE (2021)

STRANGE WAY OF LIFE

A man rides a horse across the desert that separates him from Bitter Creek. He comes to visit Sheriff Jake. Twenty-five years earlier, both the sheriff and Silva, the rancher who rides out to meet him, worked together as hired gunmen. Silva visits him with the excuse of reuniting with his friend from his youth, and they do indeed celebrate their meeting, but the next morning Sheriff Jake tells him that the reason for his trip is not to go down the memory lane of their old friendship….

THE HUMAN VOICE

A woman watches time passing next to the suitcases of her ex-lover (who is supposed to come pick them up, but never arrives) and a restless dog who doesn’t understand that his master has abandoned him.

Director

WITH

Pedro Pascal, Ethan Hawke, José Condessa, Tilda Swinton, Augustín Almodóvar, Miguel Almodóvar

Run Time

STRANGE WAY OF LIFE (31 minutes)

THE HUMAN VOICE (30 minutes)

Released

STRANGE WAY OF LIFE (2023)

THE HUMAN VOICE (2021)

Distributed by

Sony Pictures Classics

HEARING AND VISUAL ASSISTANCE

Assisted Listening

Descriptive Audio

Closed Captioning

Country

Spain

SUBTITLES

None

RATED R

for some drug content, nude images, sexual content, language, bloody images

SHOWINGS

OCT 6 | FRI

5:10, 9:10 p.m.

OCT 7 | SAT

1:10, 3:10, 5:10, 7:10, 9:10 p.m.

OCT 8 | SUN

1:10, 3:10, 5:10, 7:10 p.m.

OCT 9 | MON

5:10, 7:10, p.m.

OCT 10 | TUE

5:10, 7:10, p.m.

OCT 11 | WED

5:10, 7:10, p.m.

OCT 12 | THU

5:10, 7:10, p.m.

OCT 13 | FRI

NO SCREENINGS

OCT 14 | SAT

1:10 p.m.

OCT 15 | SUN

1:10, 7:10 p.m.

OCT 16 | MON

5:10, 7:10 p.m.

OCT 17 | TUE

5:10, 7:10 p.m.

OCT 18 | WED

5:10, 7:10 p.m.

OCT 19 | THU

5:10, 7:10 p.m.

DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT

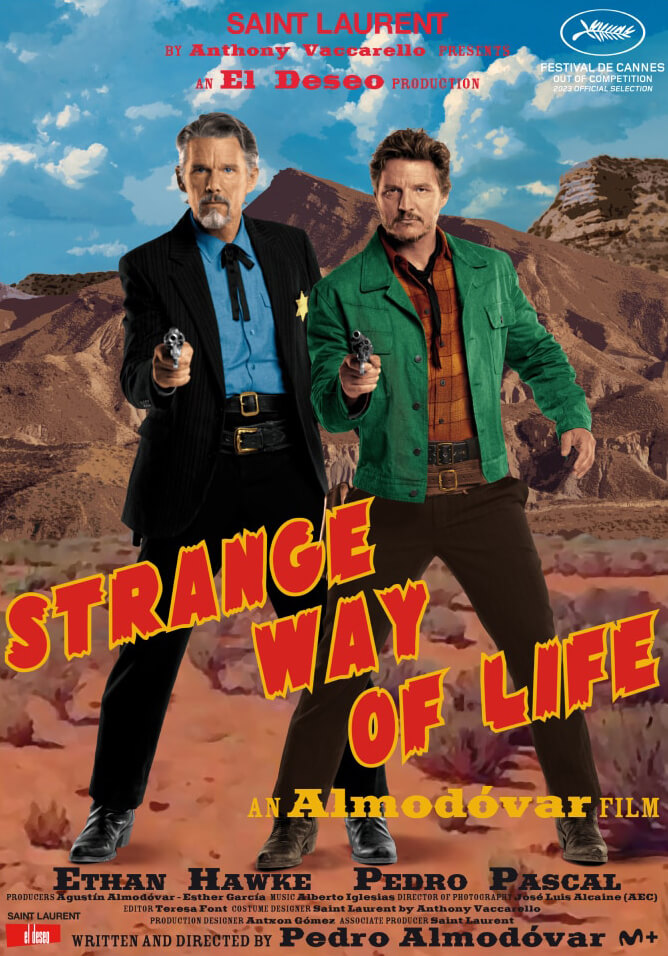

A man crosses the desert that separates his ranch from the town of Bitter Creek on horseback. He is going to visit Sheriff Jake, a friend from his youth, when both worked as hired gunmen. The action takes place in 1910, and the two men are in their fifties. Silva (Pedro Pascal) is of Mexican origin, a solid guy, emotional, elusive, a cheat, if necessary, warm. It’s been twenty-five years since he last saw Sheriff Jake (Ethan Hawke), blond, strict, cold, inscrutable, almost the opposite to Silva. That night, at the Sheriff’s house, they eat a meat stew Jake has cooked, they drink, and they make love, all of it in abundance.

The next morning, Silva wants the party to continue, but he finds a stony Jake, who is nothing like the man from the night before. (This was the first thing I wrote, the sequences that follow that orgiastic night in which both characters confront their past and their present in totally different ways.)

This is the heart of the story: the argument while they get dressed the following morning. In this argument, the ulterior motives are revealed (as well as the passion that they lived when they were younger, and that is still beating within them, even though Jake doesn’t want to admit it once they are sober). Jake has to go after a murderer who, according to an eyewitness, was Silva’s son. And Silva has to intercede for him, trying to convince Jake that his son is innocent and that he should stop searching for him. All this, the sheriff’s duty as opposed to a father’s grief, mixed with reproaches and declarations of love from two lovers who haven’t seen each other in twenty-five years and who live their lives at opposite ends of the desert. These are the ten central minutes of the film, the first I wrote. I still didn’t know what the story would be, or if there would even be a story, but my first intention was to give voice to these two middle-aged, queer men who traditionally have remained silent in a genre like the western. I was attracted by the idea of breaking that silence. Brokeback Mountain by Ang Lee is the closest Hollywood has come to telling a story about two men who love each other and talk about it, but the lovers in Ang Lee’s film are shepherds, so I don’t include the film in the western genre.

There are westerns with gay characters, like Warlock by Edward Dmytryk. The script abounds in data about the passionate relationship between its two protagonists, Anthony Quinn and Henry Fonda, but no one talks about it even though their relationship is one of the axes of the film. This turns Dmytryk’s film into a strange western or one with a badly written script. The film is only understood if both of them are lovers, but that word is never mentioned.

Although I’m a great admirer of the genre, I never thought that I’d end up making a western. I greatly enjoyed this shoot, despite the unbearable temperatures of the hottest summer in our history. We filmed in a town built in Almeria for Sergio Leone as a set for his legendary dollar trilogy, with Clint Eastwood. (The Good, The Bad, The Ugly; For a Few Dollars More and A Fistful of Dollars). The passing of time, fifty years of it, has given authenticity to the place, today being dusty and old. The typical artifice of what had been a film set fifty years ago, built back then only weeks before shooting, had now disappeared.

It was also a thrilling experience to work with Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal, both extraordinary in their respective roles.

As for the décor, I have respected the rules of the genre without falling into any anachronistic temptation, except for the song at the beginning, with the voice of Caetano Veloso and the angelical face of Manu Ríos, which gives the film its title.

For the choice of paintings on the walls of the two most important sets, the interior of the sheriff’s house and the ranch where Silva lives, I have turned to artists of the time. In Sheriff Jake’s house there are several paintings by Maynard Dixon, one of the first artists, if not the first, to paint landscapes from the American West, with native Indians and cowboys. For me it has all been a discovery, his work possesses a coloring untypical of the time that brings it close to pop and at times to impressionism. There is also a portrait of the artist Lily Langtry, very famous at the start of the century, who actually made a silent film and whom Ava Gardner plays in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean along with Paul Newman. The other great artist who appears on the walls of the ranch is Georgia O’Keefe, the Mexican landscape that hangs over Silva’s bed.

Saint Laurent by Anthony Vaccarello was in charge of the entire wardrobe. We took our inspiration not so much from the reality of the time but from cinema, how actors were dressed in westerns between 1900 and 1915. If anyone wonders about Pedro Pascal wearing a green jacket, I recommend watching Bend of the River by Anthony Mann, where James Stewart wears an identical green jacket. And I have a lot of respect for Anthony Mann and James Stewart.

We are also inspired by Veracruz (Robert Aldrich), specifically for the outfit worn by Silva’s murderous son Joe. It is inspired by Burt Lancaster, all black.

And Sheriff Jake, he’s in a suit, with a vest and bola tie, like almost all the sheriffs in the Westerns I have watched. Kirk Douglas is one of the models, whether playing a sheriff or a card player, Gun Fight at the OK Corral or in Last Train from Gun Hill, both by John Sturges. I have re-watched many westerns so as not to fall into anachronisms and the truth is that the male wardrobe has changed very little, the sheriff is always the most elegant, usually with a suit, waistcoat (the fabric of the waistcoat was the only thing that allowed you some fantasy, with shiny damasks), shirt and around the neck a bola tie.

The rest of the male characters always wear a scarf around their necks, in different colours and patterns, a checked shirt and a waistcoat. The dresses of the Mexican prostitutes are inspired by El Dorado (Howard Hawks). I have done my research with a multitude of westerns, especially Hawks, John Ford, John Sturges, Raoul Walsh, Anthony Mann, Peckinpah, Robert Aldrich, etc.

As for the narrative in general and the music, I have followed the classical canon. Despite the fact that in Spain we have a great tradition of spaghetti westerns, more than a hundred were filmed in the 60s and 70s. I have not been inspired by any of them and the composer Alberto Iglesias has avoided Ennio Morricone, who would have been the easiest reference.